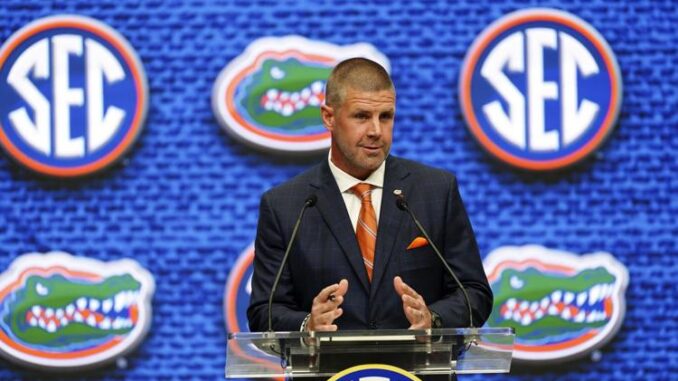

When Billy Napier first got the call about the open Florida coaching job, he asked himself a question: “How did Florida end up there?”

- “There” was not only 13 years removed from its last national championship and its last SEC title, but far behind rival Georgia

, now a national power. Florida fans had been accustomed to winning championships. Napier grew up in Georgia watching Steve Spurrier dominate the Bulldogs.

“What do we need to do,” he wondered, “to right the ship and maybe change the attitude and approach?” Napier poked around to see what was wrong with the program and what would need to be done to fix it. Satisfied the administration would help him modernize the football program, Napier took the

Now headed into Year 3, Napier has overhauled everything, from the roster (only 12 players remain from his first team) to staffing, organization and approach. The problem is the on-field results have not yet followed, putting an even larger spotlight on Napier — who is 11-14 at Florida — and the Gators as they head into their highly anticipated opener against rival Miami on Saturday.

“I’m not a fool,” Napier said when asked about people who think the clock may be ticking on his tenure. “Part of leadership is you’ve got to have some self-awareness, and you have to make tough decisions. You have to make necessary changes. We’ve done

The story at the moment is about a Florida program that has been on a roller coaster since Urban Meyer stepped down following the 2010 season. Will Muschamp, Jim McElwain and Dan Mullen all found brief periods of success — each won at least 10 games once — but none of them made it a full four seasons as head coach.

As Florida struggled to find stability at head coach, Kirby Smart elevated Georgia to a national championship contender in short order, turning the tables on a rivalry the Gators dominated in the 1990s and 2000s. In nine seasons with the Bulldogs, Smart has lost to Florida just twice. That has only added to the consternation among a Florida fan base eager to see a return to success.

The coaching transitions and slip from atop the SEC East affected recruiting, too. Since 2015, Florida has signed just two recruiting classes ranked in the top 10 — in a state known as a recruiting hotbed. The Gators are now recruiting players who were babies the last time Florida hoisted the national championship trophy.

Something more likely to be top of mind: Florida has posted three straight losing seasons for the first time since the 1940s and failed to make a bowl game last year for the first time since 2017.

“Once upon a time, there was a standard out there that we were the best of the best, and we are working to get back to that,” running back Montrell Johnson Jr. said during SEC media days, before minor knee surgery in August left his status for the opener in doubt. “That kind of makes me mad at times that we haven’t upheld it.”

When Napier made his calls during his interview process to find out why Florida had not won consistently enough, he learned the Gators had fallen behind with both their facilities and budget and were woefully behind from a recruiting, staffing, organization and sport science perspective.

His predecessors worked out of the same offices and meeting rooms inside the football stadium that had been used for decades. Players had to walk to and from practice fields located a quarter mile away and across a busy main road from their locker room inside the stadium. Mullen spearheaded the drive to get a $85 million standalone football facility built — it opened in 2022 and connects to the indoor practice facility.

Napier also asked for a significantly larger staff. The team’s support staff went from 45 people to 62. Florida has increased its assistant coach salary pool nearly $3 million to $7.5 million; another $5.3 million has gone to support staff.

The recruiting budget also has mushroomed to $2.89 million — after ranking No. 14 among SEC schools in Mullen’s final year, when the budget was $900,000. According to the latest athletic department operating budget in 2022-23, Florida spent $90.2 million on football.

Now Florida is in line with other SEC schools after years of complaints that these two specific areas were holding the program back. As one person familiar with the program pointed out, Napier has been given everything he wanted. But the on-field results are not there yet. Napier points to the rapidly changing college football landscape — including transfer rules and NIL — as one reason.

“I knew it was going to be very challenging because in our league, you’re chasing the top of the mountain,” Napier said. “To get there, it takes multiple cycles. The evolution and the chaos of our sport in the last couple of years is what’s been challenging.”

What has not helped is the way Florida has played. In Year 1, Florida had future No. 4 pick Anthony Richardson but won just six games. Last year, special teams gaffes turned the Gators into a punchline at times. Napier never hired a special teams coordinator, and mistakes cost Florida in multiple games. Against Utah in the season opener, the Gators got a penalty after two players wearing the same number went onto the field during a punt, resulting in a penalty. The Utes got a first down and eventually scored on the drive in a 24-11 victory.

Later in the season against Arkansas, the field goal unit was coming onto the field as the offense was trying to spike the ball at the end of regulation to set up a game-winning field goal. The penalty forced a longer kick, which Trey Smack missed. Florida ranked in the bottom four in the SEC in field goal percentage (.750).

And though the Gators made improvements on defense, they struggled on that side of the ball as well. They allowed Missouri to convert a fourth-and-17 with 38 seconds remaining, leading to a last-second field goal to give the Tigers a come-from-behind win. Florida ended last season on a five-game losing streak. In three of those games, the Gators had a fourth-quarter lead.

To address the issues, Napier overhauled his staff headed into 2024. Joe Houston came from the New England Patriots as an analyst, specifically focusing on special teams. Ron Roberts came in as co-defensive coordinator and linebackers coach, a veteran presence to help Austin Armstrong, the youngest coordinator in the SEC at 31. Napier also hired a new strength and conditioning coach and nutritionist.

“We’re close,” Napier said. “We’ve got a good thing going. I think maybe what you hear on the outside is not necessarily what it’s like on the inside. So, we’re anxious to get out there and play this year. This is the best team we’ve had since I’ve been here.”

Off-field headlines have not helped, either. Napier and two co-defendants are the subject of a lawsuit filed by former Florida signee Jaden Rashada over a failed NIL deal in 2022; Napier has said he feels “comfortable” with his actions and has filed a motion to dismiss the suit.

Florida athletic director Scott Stricklin has said he fully supports Napier, telling reporters at SEC spring meetings in May after Rashada filed his lawsuit, “I’ve got a tremendous amount of trust for Billy, not only who he is as a person, but how he conducts himself and how he treats other people.”

In addition to the lawsuit, Florida lost several high-profile players to the portal, including Trevor Etienne, who ended up at rival Georgia, and Princely Umanmielen, who went to Ole Miss and has publicly criticized the Florida strength program.

The focus in Gainesville is on the players who have opted to stay. Napier points to the team leadership, starting with quarterback Graham Mertz, who returns for a second and final season with the Gators after transferring from Wisconsin in 2023. Though Florida signed elite prep quarterback DJ Lagway, the No. 8 player in the ESPN 300, Mertz is entrenched as the starter.

Mertz had the best season of his career in 2023, completing 72% of his passes while throwing for 20 touchdowns and a career-low three interceptions. One opposing coach praised the job Mertz did last season, calling him a difference-maker. Mertz, though, was not satisfied with his team’s losing record.

“You go back and you just turn on the games we lost, we just didn’t execute,” Mertz said. “We had too many penalties. We might have made the wrong read on a play. There are so many different things. We needed to get better, and that’s where I’ve seen across the board everybody’s been putting in that effort to hold up their end of the bargain.”

Still, it is impossible to talk about Florida without addressing Napier and his long-term future. The Gators’ schedule this year is ranked among the toughest in the nation with four games against preseason top-10 teams (Georgia, Texas, Ole Miss, Florida State) and four others against teams in the top 25 (Miami, Tennessee, Texas A&M, LSU).

Heather Dinich and Paul Finebaum explain why Florida’s November schedule poses a hefty challenge for Billy Napier and the Gators.

Those familiar with the program said they knew the rebuild would take time because of the program Napier inherited, and because of the timeline of the vast overhaul he laid out. Napier would be owed a $25 million buyout if Florida decided to make a change after this season. The Gators have spent $20 million to buy out McElwain and Mullen. Would there be an appetite to keep spending money to get back on the coaching carousel for a fifth time in 14 years?

Three people familiar with the program said they believe Florida cannot keep hiring and firing coaches every four years — it will only keep setting the program back.

“I don’t think he has to do too much to save his job because there’s so much invested in the whole staff and everything,” Spurrier said. “I hope we can have a winning season. I predicted a winning season and [a win in] a bowl game. If we can do that, I think that would make everybody happy right now.”

Napier says he understands the speculation about his job security comes with his position, and that is not unique to Florida.

“Florida is a lot like some of the other places I’ve worked,” he said. “When it’s good, it is phenomenal. When it’s bad, it’s horrendous. So, I think that’s the leadership challenge — trying to stay objective and stay steady and really evaluate things for what they are.” To that end, he said, “We’ve got work to do, and we’re in the middle of that.” Even if outsiders have put him on a proverbial “hot seat,” that term does not exist inside the Florida athletic department. Napier says he feels confident that those with decision-making power are behind him.

“You’ve got to deal with the outside noise, but you know the administration, you understand the heavy hitters, the big investors, they’re fully behind you,” Napier said. “They’re helping you solve problems. They’re invested in your team.”

In response to the idea coaches are no longer allowed enough time to build their programs, Napier said: “When you really look at college football, how many times has [winning right away] happened? Very rarely. Depending on the roster you inherit and the league you compete in, all those things matter. We’re chasing the 1% here, so it’s going to take some time to get there.”

Napier harks back to his late father, Bill, a high school football coach who inspired him and his brothers to become football coaches. Bill Napier was interwoven into the fabric of their community in Chatsworth, Georgia, as the winningest coach in Murray County High history.

“My dad, he wanted to win because he wanted that community to be proud,” Billy Napier said. “I’ve met former players, I’ve met investors, I’ve met die-hard Gators on the road in the springtime. That’s motivating to me, to get this right so that these people can wear their orange and blue and be proud of it again.”

If he does that, nobody will have to ask that question that he asked himself three years ago.

LINCOLN, Neb. — In his first college game at Nebraska, Dylan Raiola led the way.

He walked through the bright lights, strobes and smoke and stared straight ahead as his teammates followed. His path was lined with fans clutching their phones to capture something special. He nodded his head and raised his right hand, gesturing to say bring it on.

Nebraska’s freshman phenom quarterback was out in front for the first Tunnel Walk of the season onto the Memorial Stadium turf, offering promise of a more thrilling future for the program.

Dominic Raiola, Dylan’s father and a former Cornhusker himself, was overwhelmed. From the team’s unity walk through campus to pregame warmups to the sheer number of fans in his son’s No. 15 jersey, it brought Dominic back to 1998, reliving all his firsts inside this historic stadium.

“I know it’s more than 25 years later, but man, it’s so cool that he gets to experience this and make it his own,” Dominic told ESPN. “It’s a freaking special place, man. It’s not like everywhere else.”

His son took the field against UTEP and showed the world what Nebraska coaches and players have seen from the five-star signee since January: elite arm talent, excellent poise, extreme potential. Raiola threw for 238 yards and two memorable touchdowns while calmly guiding his team to a 40-7 rout. Wide receiver Jahmal Banks said Raiola’s “killer mentality” was on full display in his debut.

“He’s been having that in his eyes since he got on campus,” Banks said. “Like, ‘I’m humble, but I’m him.'”

In an era in which 80 college football teams found their quarterbacks in the transfer portal, Raiola was the lone true freshman starting QB for a Power 4 team in Week 1. The 19-year-old doesn’t look, act or play like one. He’s a 6-foot-3, 230-pound passer with rare gifts, an uncommon work ethic and all of the pedigree as the son of a Husker Hall of Famer and NFL great. He’s been drawing comparisons to Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes on social media for months. This Saturday, against Hall of Famer Deion Sanders and Colorado (7:30 p.m. ET), he plans to show he wasn’t just raised for this. Dylan Raiola believes it’s in his blood.

“It was always tugging at my heart,” he said on signing day.

He could’ve been the next great at Ohio State. He fell in love with Georgia’s powerhouse program. But in the end, Raiola surprised even his own family by choosing to help coach Matt Rhule lead a revival at Nebraska. Kids his age weren’t alive for the days of Husker dominance. The five-time national champs haven’t won a conference title in his lifetime, haven’t gone to a bowl game since 2016.

Raiola chose to buy into a bold vision. He believed in himself enough to go where he could make the greatest impact. You could already see it on Saturday.

“I think it finally hit him: ‘I’m here,'” Dominic Raiola said. “He told me something cool about walking out of the Tunnel Walk. He said he told himself, ‘It’s time for a new era of Nebraska football.'”

BEFORE THE CHAOS kicked in, the Raiolas huddled together on the Memorial Stadium sideline for their pregame ritual. Dylan held his helmet in his left hand and ducked his head in as his mother led the family in prayer. Yvonne, Dominic, Taylor, Dylan and Dayton were finally together again.

Mom started this tradition for Dylan’s high school games and Taylor’s volleyball matches. But here they were, arm in arm, in front of more than 86,000 inside a venue steeped in familial legacy.

Dominic’s name and number are on the walls of this 100-year-old stadium, just below the scoreboard alongside all-time greats Will Shields, Grant Wistrom and Eric Crouch. He took immense pride in playing for Nebraska, arriving from Hawaii during the program’s heyday and devoting himself to maintaining the standard of excellence.

Dominic battled and scuffled with Wistrom and Jason Peter as a young lineman and put in the work to become the Huskers’ center as a redshirt freshman, a rarity in its venerated “Pipeline” era. Raiola made a name for himself as a two-year starter and consensus All-American with his fiery intensity and a school record 140 pancake blocks in 1999. Legendary Nebraska offensive line coach Milt Tenopir called him the finest center he coached in his 29-year tenure.

He agonized over his decision to enter the draft after the 2000 season. Dominic didn’t know if he was ready to leave a program that had done so much for him, but he was ready to be a pro. The second-round pick found a new home in Detroit, spending his entire 14-year career with the Lions and starting a franchise record 203 games.

Dylan was born in 2005 and grew up around that NFL locker room, running around playing with Matthew Stafford, Calvin Johnson and so many welcoming teammates. Dominic got calls and texts from plenty of them over the weekend. He knows that environment showed his son what was possible.

In their household, faith and family came before football. “Family is everything for us,” said Nebraska offensive line coach Donovan Raiola, Dylan’s uncle. The extended Raiola clan is a tight-knit unit, their support for one another unyielding. Dominic likens the loyalty and brotherhood ingrained in their family heritage to the line from “Lilo & Stitch”: Ohana means family, and family means nobody gets left behind or forgotten. When he talks about the Nebraska legacy his son is continuing, it’s never been just about himself.

“When you wear your name on the back of your jersey and walk around town, your last name represents a lot of people, not just yourself,” Dominic said. “My name’s in the stadium, but that ain’t just my name. It represents a lot. You are carrying the torch of a lot of people, wearing a coat with a lot of names on your back.”

But Dylan grew up watching sports as a kid, not Disney movies. Taylor, the oldest, played volleyball at TCU and is now working in Nebraska’s recruiting department. Dylan always preferred baseball growing up and played travel ball before embracing football in high school. Dayton is up next, starting at quarterback for Buford High School in Georgia as a junior. The kids spent much of their childhood together on courts and fields.

When he got into high school, Dylan started working with health and performance trainer Bobby Stroupe and quarterback trainer Jeff Christensen. One trait that was easy to see from the start? Raiola was blessed with a “cannon,” as Stroupe put it, and an uncommon range of motion in his shoulder blade.

“That kind of stuff is handed out by God most of the time,” Stroupe said.

In that way, the Mahomes comparisons are undeniable, even if Dylan pushes back on them at times. They’ve met through their time spent training with Stroupe and Christensen and are friendly. Mahomes calls him “cuzzo” and has been supportive from the start. Dylan says he wears 15 as a tribute to Tim Tebow, but the Mahomes inspirations in his game and style easily stand out to any observer. Like the Chiefs superstar, Raiola can extend plays, throw against the grain and complete off-platform passes others cannot.

He flashed it in the first quarter against UTEP, converting on a third-and-11 by side-arming a dart in a tight window to receiver Isaiah Neyor for a 16-yard gain. It was the kind of conversion Mahomes has delivered time and time again and evoked instant comps to the three-time Super Bowl champ.

“He was like a freakin’ surgeon,” Nebraska offensive coordinator Marcus Satterfield said of Dylan. “It was amazing to see him and his maturity way beyond his years.”

“Everyone looks at him like a freshman,” Donovan Raiola added. “But I don’t.”

SOON AFTER RHULE accepted the Nebraska job in November 2022, he started hearing about the QB everybody wanted him to flip.

“I remember Trev [Alberts] saying pretty early on, ‘Do you think we’ll ever have a chance at Dylan?'” Rhule told ESPN.

Like the rest of the fan base, Nebraska’s now-former athletic director recognized this recruitment was of the utmost importance. Rhule, coming off a three-year stint with the NFL’s Carolina Panthers, had a ton of catching up to do in recruiting. But he was quickly brought up to speed on the Raiolas and what they meant to Nebraska.

In the final weeks of a 2½-year recruiting process, Dylan came to appreciate what the opportunity truly meant.

Georgia was his first scholarship offer in the summer of 2021. Nebraska offered a week later at a summer camp. And then everybody else did. Dylan was anointed as a top-50 recruit in his class before he’d started a varsity game. After one high school season, he was bumped up to No. 1 recruit status in the spring of 2022. That’s a long time to live with those expectations.

Nebraska never stopped chasing him. The courtship began with Scott Frost, who hired Donovan Raiola away from the Chicago Bears at the end of 2021, but he and his staff were on the hot seat. “It was a little rough patch at Nebraska, some unsettled times,” Dominic said. Dylan made an early commitment to Ohio State in May 2022 but decided to reopen his recruitment in December, three weeks after Rhule landed in Lincoln.

Kirby Smart pushed hard and had just won consecutive national titles. Lincoln Riley made him USC’s top priority. At that point, the Huskers were selling hope more than hype. Rhule was impressed by Dylan’s humble, kind-hearted nature right away.

“How we had always recruited him was I said to him: ‘I made the decision to come here. I show up here and I see a program that’s down, but I see a program that’s been at the top,'” Rhule said. “‘I see an opportunity for me to come make a difference at a place that matters. So why don’t you come here and make a difference at a place that matters? The easy thing would be to go to the place that’s already winning.'”

After taking more visits in the spring, Dylan picked Georgia last May. Dad wasn’t surprised.

“I knew he loved Georgia the whole time,” Dominic said. “It almost felt inevitable it was going that way. I mean, how could you not?”

Rhule and his staff moved on, turning their focus to in-state passer Daniel Kaelin and flipping him from Missouri. The Raiola family relocated from Arizona to Georgia ahead of his senior year and attended every Bulldogs home game last season, most of them blowouts.

But on Sept. 30, they made a curious choice. The Raiolas flew back to Lincoln for Nebraska’s game against Michigan. The trip was intended to be for Dayton, who has a Husker offer, but Dylan tagged along. They watched the No. 2 Wolverines shred Nebraska 45-7. “It was ugly,” Dominic said. The showdown with the future national champs showed just how far the Huskers were from being a Big Ten contender. “You saw us at our worst,” Rhule told the Raiolas. Dylan gave no indication he was rethinking his decision, and Nebraska’s staff did not push him. But his uncle hadn’t totally given up.

“I didn’t want to feel like it was over, but you never know, right?” Donovan said. “I was holding out hope.”

Dylan kept his focus on his senior season at Buford. Smart and Georgia OC Mike Bobo came over for their in-home visit with the Raiolas on Dec. 5 to close out the recruitment. Four days later, Dylan came to his parents and confessed he was still thinking about Nebraska. He wanted to take one more visit. Dominic said he and Yvonne were more puzzled than elated. Why now?

“I’ll tell you what changed in his heart,” Dominic said. “He knew he had a different kind of talent. He told us: ‘God has bigger plans for me than just going to Georgia and being the next five-star and being in line to win the national title. God has different plans for me.’ And those plans were to go to Nebraska and do something hard.”

Rhule insists he didn’t see it coming.

“I remember when he called me,” Rhule said, “I was like, ‘Really?'”

Dylan saw past an offense that finished last in the Big Ten in passing yards with the second worst turnover margin (minus-17) in the sport, a team that kept finding ways to lose close games even under a new front office. He liked Rhule and the culture he was trying to establish. He felt a different vibe during the Michigan game, even in defeat.

“Nebraska’s the only place that you can bring back and it can mean something more than just we won a game or won a championship,” Dylan said this spring. “I think if we do that here, it’ll make a lot of people happy and be special.”

On the following Monday, the news of Dylan contemplating a flip leaked out. Nebraska had been courting experienced transfer QBs and got Ohio State’s Kyle McCord on campus for a visit. Then they backed off. By the time Dylan got on the plane to Nebraska for his weekend official visit, it was a done deal.

Nebraska offensive tackle Teddy Prochazka was at home doing laundry when he first heard the Raiola rumors.

“I thought it was fake,” Prochazka said. “Someone texted me like, ‘Yo, check Twitter, is this real?’ I’m like, ‘Dude, I have no idea.’ And then sure enough, a few weeks later, he was committed. Donny kept it close to the chest. Everyone was just kind of like, ‘I don’t know, it could be happening …'”

The Elkhorn, Nebraska, native understood the magnitude of the moment.

“One of the biggest things is it gets people talking about Nebraska,” Prochazka said. “We deserve to be in the national spotlight. We want to play in those big games and be talked about. That definitely got the word out that, hey, Nebraska’s got something building over here.”

EARLY MORNINGS AND late nights. That’s how Dylan got ready to start.

Satterfield, his offensive coordinator, calls him a young pro. He was purposeful throughout the process of installing Nebraska’s offense and instilling confidence. Rhule got used to early morning texts and finding him in the weight room doing extra workouts or stretching at 6 a.m. The freshman would ask permission to break curfew during fall camp to keep working. He’d write and rewrite notes and play calls late into the night to get the cadence and rhythm down. Tight end Thomas Fidone said Dylan finds the magic in the minutiae.

“He’s just obsessed with trying to be really, really, really, really good,” Satterfield said.

The starting job had to be earned along with the respect of his new team. Dylan took his receivers down to Texas in June to train together. He took his linemen out for pizza and wings and they ran up a big bill. They’d gather at his uncle’s house to watch UFC fights and play video games.

“The team is everything to him,” Donovan said. “He’s a very thoughtful, authentic, genuine guy. He’s always been like that since he was a little kid. Every team he’s been on, it was always the team first.”

Added Rhule: “He doesn’t have to be the focus of everything.”

Players have been wowed by his composure, steadiness and poise in practice. Everyone got to see it on Saturday. Dylan checked a play and checked again and reloaded on a third-and-5 to get to an Emmett Johnson run that broke for 42 yards. When he did so in his first spring practice, flipping a play to adjust for a blitzer, Rhule joked that it brought a tear to his eye. Dylan got his first two-minute drill late in the first half against UTEP and let it rip, tossing a perfectly placed back-shoulder touchdown throw to Banks with 8 seconds left.

You don’t see many freshmen doing what he’s trying to do these days. Back in 2019, it wasn’t unusual to see Jayden Daniels, Bo Nix, Sam Howell, Max Duggan and Kedon Slovis all starting as true freshmen. The increasing popularity of the portal ever since then has led to far fewer play-right-away opportunities at the highest level.

In fact, over the past four seasons, only one top-50 QB recruit has started 10-plus games as a freshman for a Power 4 squad: Georgia Tech’s Jeff Sims, who later transferred to Nebraska and then Arizona State. Even if it’s the plan going into the year, getting through the season can be easier said than done. Last year, five-star recruit Dante Moore was UCLA’s opening day starter. He was benched after five games. Now he’s at Oregon.

In Dylan’s case, there won’t be training wheels. Satterfield didn’t hand him a pared-down playbook. They’re giving him trust to run their system, progress through his reads, make mistakes and improve.

“How we want him to play when he’s a junior, we’re going to start Day 1 that way,” Rhule said. “We’re not easing into anything.”

But here’s an important distinction: Nobody is asking the kid to fix Nebraska football all by himself.

Rhule has coached freshman starting QBs before, but he’s never had a five-star. He’s been measured in his public praise of Dylan. The last thing he wants to do is add more pressure. He learned from working with first-round picks in Carolina and seeing the burden they felt in trying to live up to big contracts.

Rhule reminds him that when you’re Nebraska’s starting quarterback, you better be prepared to ride the highs and lows and can’t live by what others think of you. This is a fine week for the freshman to listen to that lesson. Colorado is coming to his house on Saturday night for one of the Huskers’ most anticipated home games in years. Winning this one certainly gets people talking about Nebraska.

“I want him to take everything in stride,” Rhule said. “He doesn’t have to put everything on his shoulders. He just has to do his part and have fun doing it.”

Dominic Raiola raised his son to believe no moment is ever too big if you go in prepared. When asked last week what fans could expect from him, Dylan knew the answer. The process of building up to this didn’t start with a commitment in December or a workout in January. It began the day he picked up a football.

“Buckle up,” Dylan said with a smile. “It’s going to be a fun ride.”

Be the first to comment